“Pan Tadeusz” manuscript

The first part of the main exhibition, called The Pan Tadeusz Manuscript, is a story which leads us into the Romantic era. We take our visitors on a journey, during which they will discover a few key contexts of Mickiewicz's masterwork.

On the first and second floor of the "romantic" exhibition they will find the following rooms:

At the end of 18th, and in the early 19th century, Poland gradually lost its independence, and its territory was divided between neighbouring countries. A time of uprisings, wars and sacrifices in the struggle for the country's freedom began – an era of heroic victories and spectacular failures. This was when the May 3rd Constitution was established, the Polish national anthem was written and the myth of Napoleon emerged, then faded. The fight for freedom was the main subject of Polish social thought, art and literature for over 100 years, and military opposition towards the occupiers became the obligation of every patriot. Adam Mickiewicz wrote his national epic between 1832 and 1834, when it seemed that the dream of a free Poland was gone. Historical events are one of the most important contexts of Pan Tadeusz.

Pan Tadeusz was written in the era of Romanticism in European culture. The ideal of creativity was a synthesis of the arts – reciprocal permeation of poetry, painting, music and philosophy. This idea was often discussed in Romantic salons. The word salon has an Italian origin, and initially referred to a grand, decorative hall. Gradually it became the name for an influential group of people who who shaped cultural trends. Usually managed by women, salons were popular across the whole of Europe at the time; guests included artists, scientists and politicians.

The author of Pan Tadeusz took his firts steps in the Vilnius salon held by Salomea Bécu, Juliusz Słowacki's mother. Later, exiled from Poland, the increasingly famous poet-improviser became the star of the most important European salons.

Through the biography of Adam Mickiewicz (1798-1855), one can clearly follow the dramatic stories of the Polish Romantics. The collapse of their state and loss of freedom didn't prevent the greatest works of Polish literature from being created. The artists, wandering through the world, found a path to creative fulfilment. Perhaps Mickiewicz was the greatest of them – a true European, a wanderer and pilgrim driven by the need for discovery. His journey, which began at the end of his university studies, led from Navahrudak through Vilnius, Kaunas, Moscow, Odessa, St. Petersburg, Weimar, Paris, Dresden, Berlin, Greater Poland, Lausanne and Rome to Constantinople, and lasted for half a century. Many of these experiences were echoed in Pan Tadeusz.

The knowledge of the young Romantics was based on thorough study of domestic and international classics of literature, as well as the mastery of ancient and modern languages. A Polish Romantic could rarely boast of his own or a family-owned library, but would have access to vast amounts of books during school and university education. They could also use the collections of their wealthy benefactors. Books, atlases, albums, manuscripts, drawings, etchings, maps and diaries were the sources of knowledge and inspiration. Pan Tadeusz represents a key point of reference for generations of Polish readers.

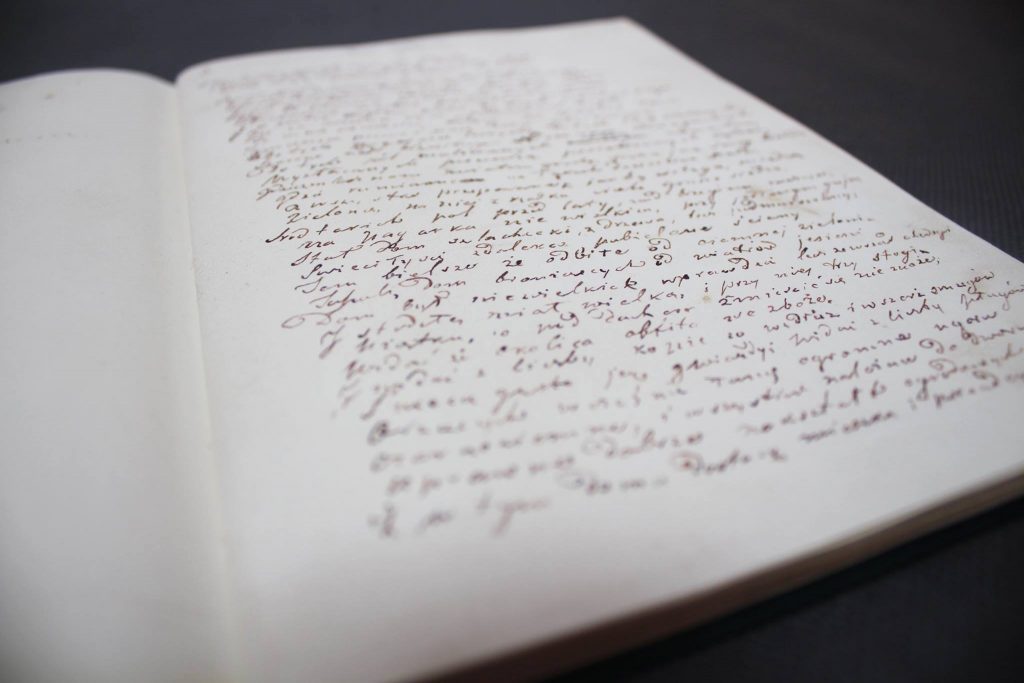

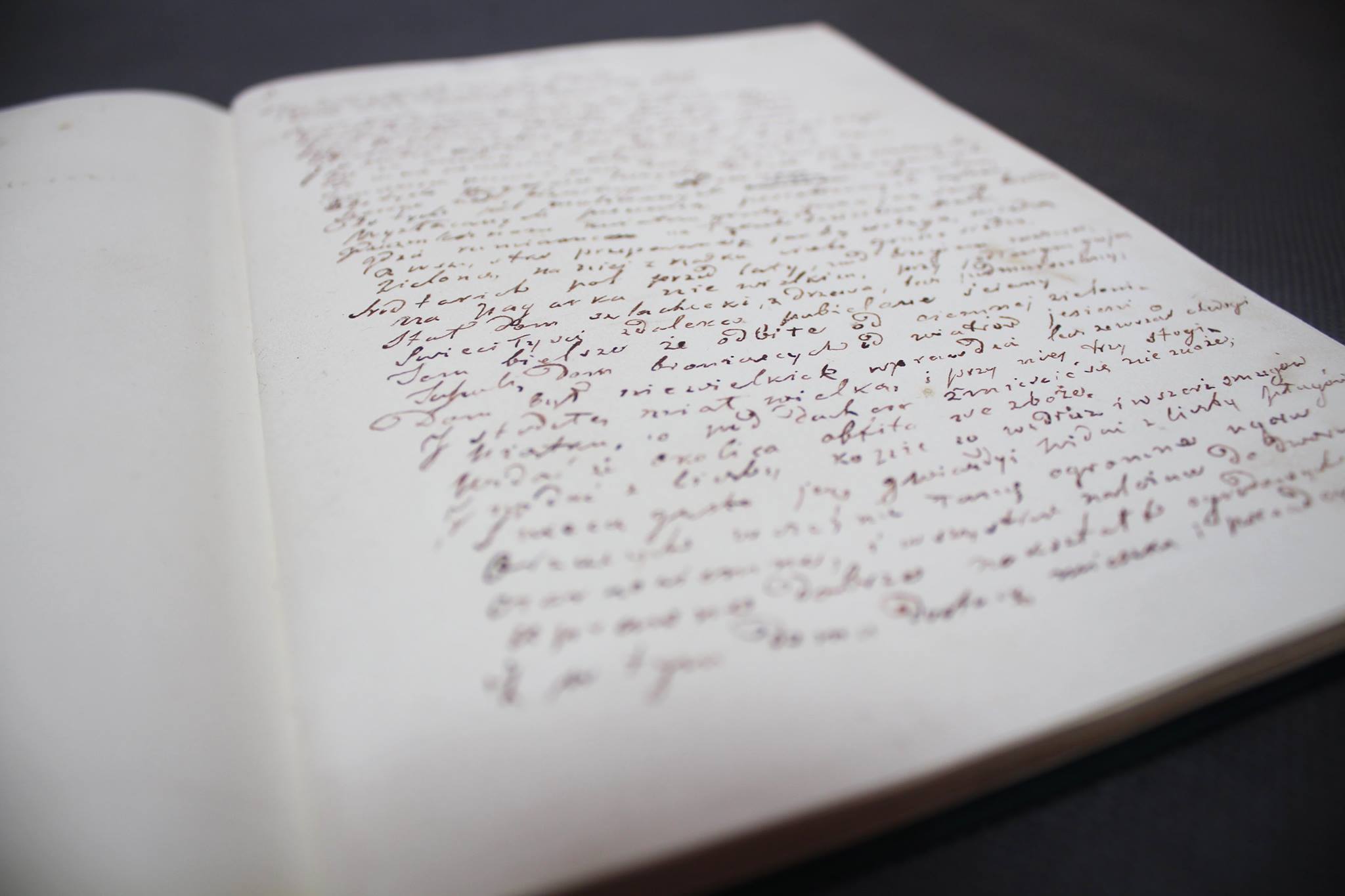

The manuscript of Pan Tadeusz is the most precious object in the Ossolineum's collection, and one of the most valuable items of Polish cultural memorabilia. It includes a notebook in a soft cardboard cover, consisting of 48 pages and other fragments, and a 91-page album with a clear rewriting of the text. The entire work is bound in red leather with gold-covered decorations. Mickiewicz began work on the poem in 1832. The last verses of Pan Tadeusz were written on 13/14 February 1834, in a rented flat above the stables on the "narrowest and dirtiest street in Paris", the now non-existent Rue Saint Nicolas d'Antin 73, near the church of the Holy Trinity.

In Pan Tadeusz, Adam Mickiewicz provided a colourful description of the customs of the nobility (the szlachta), which became a basis for Polish identity in the era of the partitions. The Nobility room presents the life of the szlachta, the originality of their customs, their virtues and merits, but also their flaws and vices. Material traces of the nobility's culture accompany us today in museum exhibitions and examples of architecture preserved in Poland and the east of the former Commonwealth. The public dimension of the culture manifested itself in attire, especially the kontusz (a type of male overcoat).

The life of the nobility was linked to the cultivation of the traditions of the family estate. Life there ran according to the rules prescribed by the nobility's customs. One of the most important elements was hosting visitors – mainly neighbours – and feasting together. Meals consisted of aromatic dishes, rich in spices, and a variety of drinks, including coffee, which was particularly enjoyed by the szlachta. The introduction of new dishes was accompanied by the specialisation of table settings and cutlery. Attire was an important aspect of daily life. Women's fashion in the early 19th century was influenced by French style, while men still preferred the traditional national costume, albeit increasingly replaced with more comfortable Western European clothing.