Exhibits

The most important exhibits of the Pan Tadeusz Museum

Exhibitions

Ebony casket with ivory inlays

In 1873, ordered by Professor Stanisław Tarnowski, owner of the manuscript of "Pan Tadeusz", the ebony casket was made to store the priceless manuscript, encrusted with ivory reliefs. The maker, the sculptor Józef Brzostowski placed ivory reliefs on the top and sides – of a bust of Mickiewicz as well as of scenes from the poem, based on illustrations by Juliusz Kossak. These are of the polonaise, the Army concert, a battle and mushroom picking.

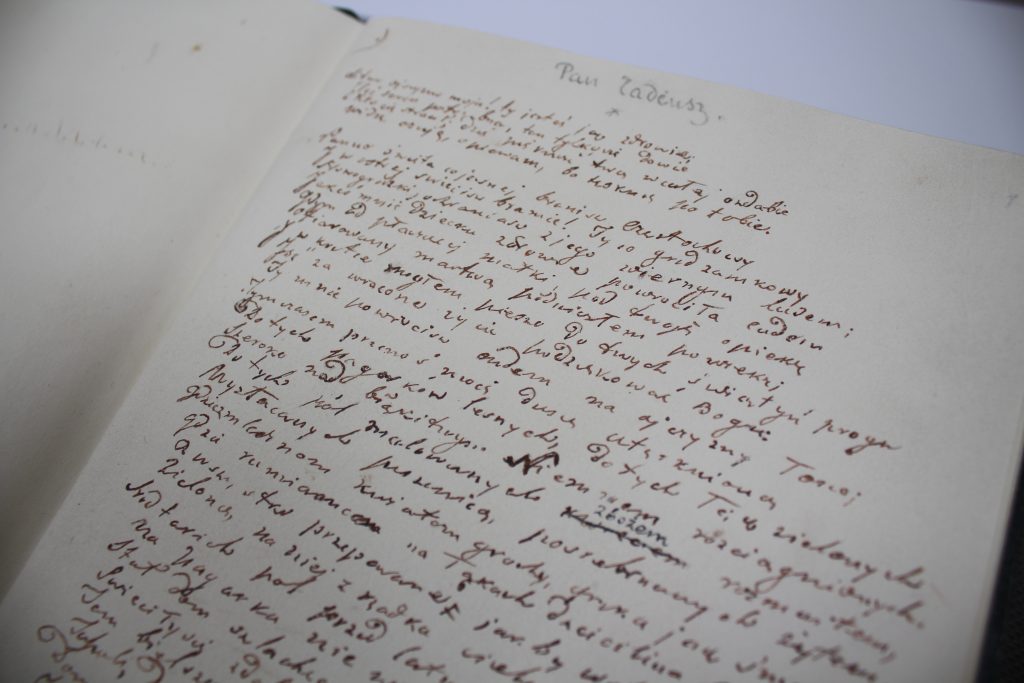

Manuscript

Manuscript of "Pan Tadeusz" – the most valuable exhibit in the collection of the Ossolineum and one of the most important relics of Polish national culture.

Mickiewicz began writing the poem in Wielkopolska, but he really got down to work on the piece in November 1832 in Paris. Work on it lasted until February 13, 1834. The poet wrote out a clean copy in a notebook with a marbled cover, then, from the 4th book, used large sheets of paper folded into four. The manuscript therefore contains: a small notebook and slightly larger bundles of sheets of paper covered in writing and folded over repeatedly.

The manuscript of "Pan Tadeusz", and so the text written by the author himself, was written using a goose quill, one which experts point out was not over-sharpened. The poets handwriting, which isn’t that legible, must have caused difficulties for the copyist, Ignacy Domeyko and the setter of the text. The manuscript was written hastily, diacritics, meaning the accents distinguishing Polish characters such as ą and ę, were often omitted. We should remember that, while the clean copy was the main source for the print version, it is not the final text. The poet made amendments while correcting the first print and also after the publication of the first edition.

Józef Mehoffer, portrait of Adam Mickiewicz, oil on canvas, 1898

Józef Mehoffer, the leading painter of the Young Poland period, at the turn of the 19th century, presented the poet in a somewhat different convention than in the hitherto dominating representations. It’s almost an official, office portrait. The calm gaze, tidy hair and neat stubble of a respectable, middle-aged man recalls more a placid official or a lecturer (which Mickiewicz,after all, was). There isn’t the concerned gaze, or melancholy soul, present in other portraits of Mickiewicz.

The peak period for paintings, sketches, reproductions and popularisation of images of the poet falls in the late 1890s. Apart from the burial of the poet’s ashes in the Wawel in 1890, the next significant pretext for making portraits of Mickiewicz was the centenary of his birth. In 1898, the entire country was swept by a wave of celebrations, of erecting monuments and creating images of the poet in innumerable versions. This portrait, from the brush of Mehoffer, most likely arose on this occasion.

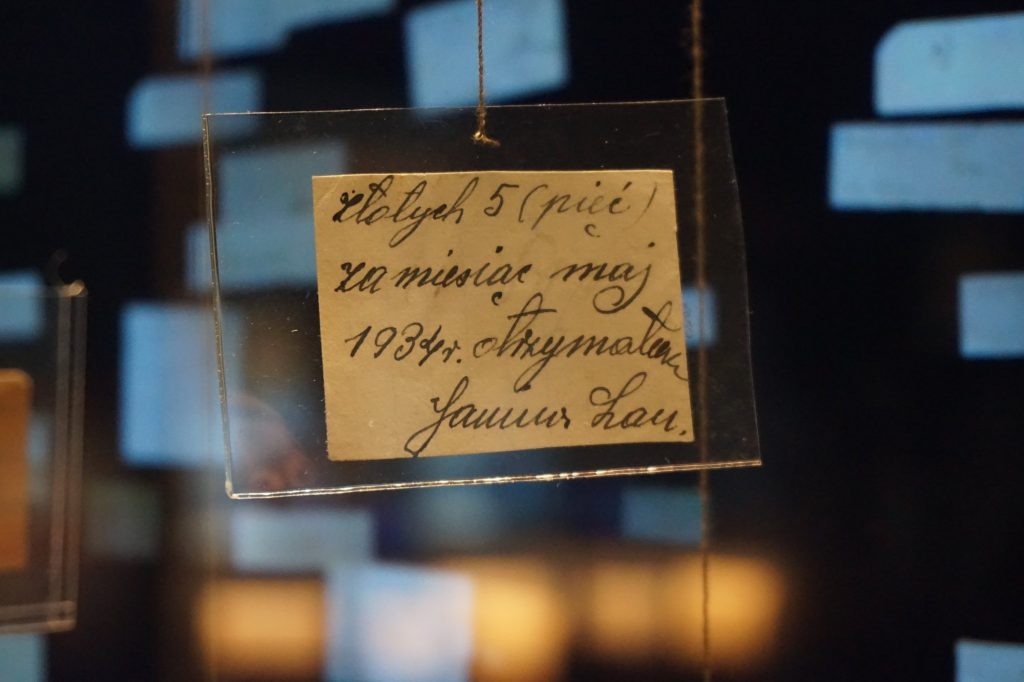

The Archive of "Felicja"

This is the only surviving proof of the help that the Council for Aid to Jews, "Żegota", gave to the Jewish people living in the ghetto or else hiding on the Aryan side of Warsaw. Each piece of paper is a receipt with an encrypted date and an amount of money. This valuable archive survived thanks to the unit’s leader, who didn’t obey orders to destroy it.

At the end of 1942, Władysław Bartoszewski was working for the Council for Aid to Jews, "Żegota". The council’s aim was to provide Jews living in the ghettos, as well as those hiding in Aryan areas, food, medicine, money, fake birth certificates and baptism cartificates. One of the "Żegota" cells was called "Felicja", and it had 340 Jews under its care. The head of the cell was Maurycy Herling-Grudziński, the brother of Gustaw, a renowned writer. The receipts for cash passed on to the in need were written on small scraps of paper, so they could be easily hidden when on the move. As a misleading element, the dates on them are moved back ten years and the amounts divided by 100.

The "Felicja" archive survived, buried by Maurycy Herling-Grudziński, going against orders to destroy the documentation. It was discovered many years after the war and in 1976 came into the possession of Bartoszewski.

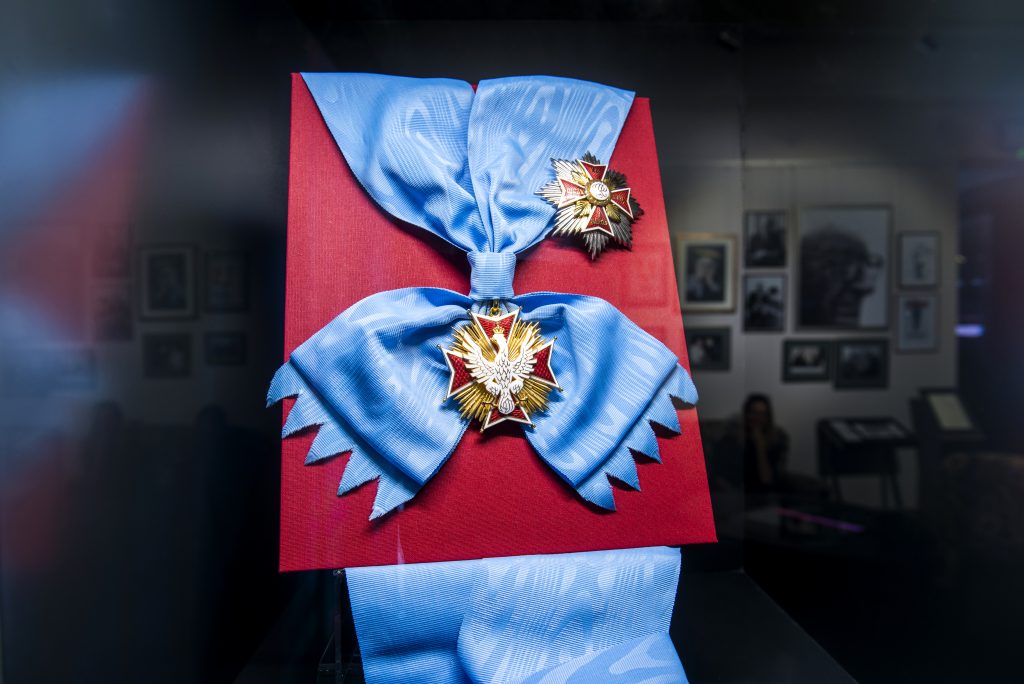

Order of the White Eagle

The Order of the White Eagle is the oldest and highest national award in the Polish Republic, given for extraordinary civilian and military services both in peacetime as well as war. It is not divided into classes. It goes to the most outstanding Poles as to the highest ranking representatives of foreign states.

The order has a long and complicated history. It was created by King August II the Strong in 1705, during the partitions, the name was appropriated by the Tsars of Russia. After Poland regained its independence at the end of the First World War the order was reintroduced, and from the outbreak of the Second World War till 1990 it was awarded exclusively, and very rarely, by the Polish Government in Exile. In 1992, in a now free Poland, it was again restored.

Władysław Bartoszewski received the Order of the White Eagle in 1995. In later years he became part of the Chapter of the Order, and in 2011 he became Chancellor of the Order of the White Eagle. Usually, receiving the Order of the White Eagle is the culmination of a long political career. After becoming a Knight of the Order of the White Eagle, Władysław Bartoszewski still had twenty years of extremely active public service before him.

Jan Matejko, "Drowned in the Bosphorus", oil on canvas 1872

Jan Matejko embodies Polish historical painting from the 19th century, so his works had special significance for Nowak-Jeziorański, although the subject of this painting is not related to Polish history. Nevertheless, in the story of this mistress of a Turkish sultan drowned in the Bosphorus a Polish element is contained. According to the legend which Matejko heard and decided to immortalise in paint, the unhappy woman betrayed the ruler with a Polish officer. The first version of the painting shown here, made by Matejko in 1872 is something of a sketch. The final version, painted eight years later, with more detailed figures, is in the collection of the Wrocław National Museum. The figure of the sultan observing the execution is seen by some critics as bearing the features of Matejko himself, and the victim drowned in the Bosphorus – those of his wife.

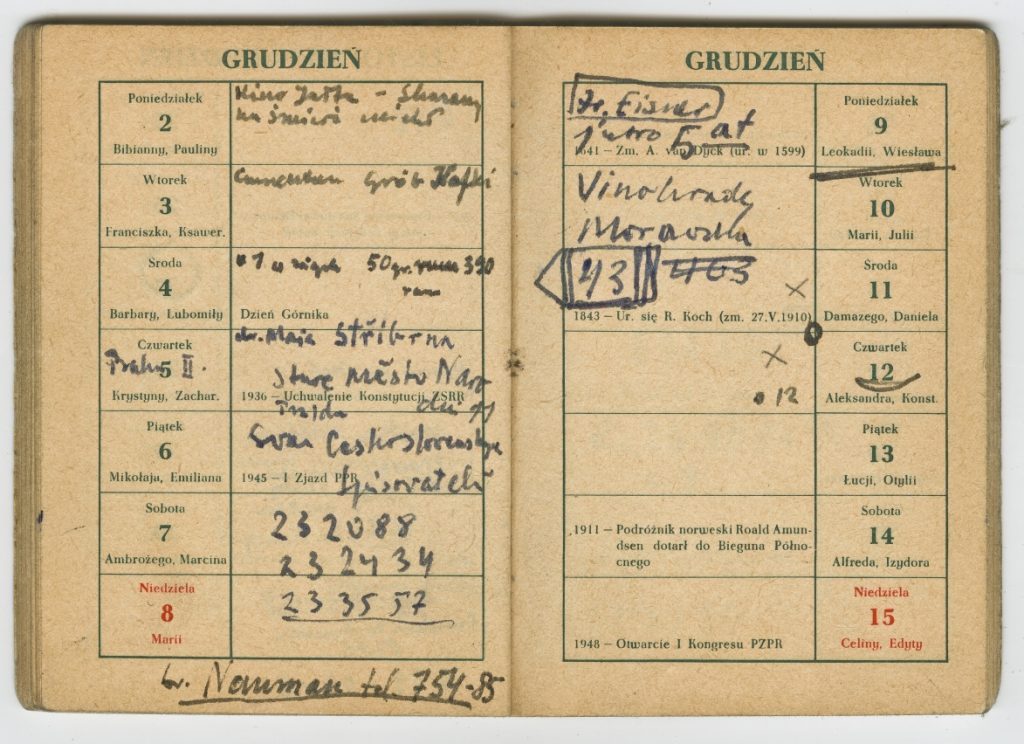

Tadeusz Różewicz’s calendar from 1957

In his small calendars Tadeusz Różewicz noted dates of meetings, telephone numbers, addresses and important events, he also wrote death and birth dates of family members, and anniversaries. Often, particularly during holidays, there are weather reports, sometimes comments on the mood, or drafts of poems. Notes in calendars were made from the beginning of the 1950s, until his death – you can see how the poet’s handwriting changes, the number of foreign travels drops, the number of doctor’s visits rises.

The poet’s desk

This is the original desk used by the poet in his office, where he wrote. Tadeusz Różewicz did not use a typewriter or a computer. He put many corrections on his manuscripts, later he also changed typescripts and prints, he also corrected already published poems. He considered himself a craftsman, and his work – manual labour.

"Woda Życia. Ewangelia według Jana" [Water of life. Gospel according to John], a copy with Tadeusz Różewicz’s notes

For all his life Różewicz was an avid reader and a perceptive commentator of the Old and New Testaments. On free copies of protestant editions of the Bible he noted the time and place of reading, there are also echoes of biblical language in his poems. Gospels belonging to Tadeusz Różewicz were translated and published by the protestant Biblical Society.

![„Woda Życia. Ewangelia według Jana” [Water of life. Gospel according to John], a copy with Tadeusz Różewicz’s notes, Ossolineum's collection „Woda Życia. Ewangelia według Jana” [Water of life. Gospel according to John], a copy with Tadeusz Różewicz’s notes, Ossolineum's collection](https://muzeumpanatadeusza.ossolineum.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/„Woda-Zycia.-Ewangelia-wedlug-Jana-Water-of-life.-Gospel-according-to-John-a-copy-with-Tadeusz-Rozewiczs-notes-Ossolineums-collection.jpg)